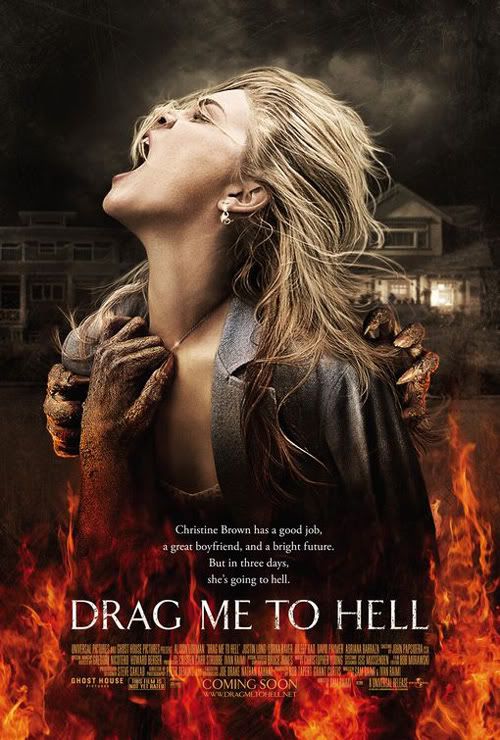

Title: Drag me to hell

Director: Sam Raimi

Language: English

Year: 2009

Critical Reception: Metacritic rating of 83, Rating of 100% from Wall Street Journal's Joe Morgenstern, 90% from Salon's Stephanie Zacharek, 80% from the Village Voice's Nick Pinkerton

Psych Index: Gender role

In Brief:Being a modern woman is never quite completely good and moral as often demanded of characters in horror films, and it is rare that a film existing in fantasy would be inspiring with its choice of such a realistic (or at least close to being as such) lead. The filmmakers may have been overly critical of this particular modern woman, but in doing so, they made her one of the most fascinating and complex leads to watch in a genre that’s not particularly known for depth. In turn, she made the film surprisingly more substantial and interesting than all the fun gags could reveal.

Comment (SPOILERS ALERT):

Drag Me To Hell (Raimi, 2009) opened as a counter-programming film to Disney/Pixar’s Up. For a horror film, especially considering the current crop of films in that genre, its PG-13 rating seemed a little suspect. How can a good horror film have anything less than a presumably envelop-pushing R-rating? What of violence and nudity that make up most of the genre? By the time our heroin, Christine Brown (Alison Lohman), engaged in her first battle with the woman who would be placing a curse upon her (Mrs. Ganush, played with ferocity and a sense of fun by Lorna Raver), it was clear that what the film may lack in nudity and gore, it made up for it in humour and over-the-top grossed out goobs.

To be sure, there was not much here in term of plot (as expected in the genre): Christine was a loan officer who, in an attempt to prove her worthiness to her boss, made a decision to shelf away compassion (or was it really guilt?) and deny an old gypsy woman of another chance to live out the rest of her life in comfort and dignity. As an act of vengeance against what she saw as a deliberate attempt to shame her, Mrs. Ganush, after an outrageously funny and suspenseful cat fight with Christine, placed a wretched curse upon her. Christine then met with a psychic, Rham Jas (Dileep Rao) who was not only knowledgeable of the curse but also knew of whom she should ask for help from – at a negotiated price of the cold cash variety. Much haunting ensued within the three days that Chrsitine had left to prevent having her soul dragged to hell by an invisible Lamia. Of course, there was also a twist ending (that we could see miles away, but it was deliciously satisfying, nevertheless), and its conclusion underlined a strong moral statement the film seemed to take a vested interest in.

The Raimi brothers knew how to imbue their picture with a sense of humour while remaining true to the traditions of the genre. This difficult balance – winking while running on adrenaline – played itself out not only with the way the picture was filmed (music, gags, cheesy lines and sound effects were in full force, intermittently interrupted by the still scenes and slow tracking shots) but also in our heroin, Christine. Women are one of horror’s favourite subjects – most of the genre could be argued to have been built on the strength of women’s thighs and other close-by regions. If the central character happened to be of the female variety, she would be expected to have the audience’s sympathy at least by the end of the film. Our horrified heroin is often violated against in some manners, and she would often have the higher moral ground compared to our villain(ess). In Christine, the Raimi brothers threw in their best twist and most biting comment in the film yet.

Christine was very much a picture of a modern woman, a determined social climber who, on sheer will and smarts, had gone from a chubby pork queen of a farm girl to a candidate for an assistant manager at a bank, with a young and devoted professor of psychology as her boyfriend (his name, Clay, suggested a certain boring malleability though – Justin Long was perfectly cast for once). In her first fight with Mrs. Ganush, after locking down her car windows and watching the old woman flail seemingly helplessly against the glass, she yelped victoriously from inside the car: “I BEAT you!” She was eager for self-congratulations throughout the film – she wanted so badly to beat the odds that she would prematurely celebrate any inroads. There was a certain glee in her tenaciousness and willingness to go the necessary distance to survive. No doubt in her mind she was a worthwhile heroin who would overcome and rise above life obstacles. The events that unfolded would show her to not be completely in sync with what she would like to think of herself, however.

In the course of the film, Christine painted herself – in words, mostly - to be a compassionate, grateful woman: she professed to be a vegetarian who loved animals (see how that fared out in the film), she confessed her wrong-doings to her safety net of a boyfriend (to which he replied ‘you’re such a good heart’), she acknowledged her background (Clay’s mother found her admittance to be a sign of a backbone, when it could be interpreted as another instance of her blaming others for her troubles) and she showed hesitation in both times she had to make a difficult moral decision (at first, with Mrs. Ganush, and later, with the handling of the cursed button). However, her good deeds seemed to stem from either guilt (her name, Christine, was a bit of a giveaway) or self-interest (survival), as would be the case for most ordinary human beings.

In the relative calm of an ordinary life, it was easy for her to be a good Christian. After all, it’s easier for most of us to be good citizens when the structure is there to encourage moral acts: presence of a recycling bin would encourage more recycling at a given location, for example. It’s easier to give away millions when you earn trillions. When you have all the time in the world to drive home, allowing someone to bud in a busy traffic line may not be such a big deal. If Christine was not in the position to climb the corporate ladder, she may have given Mrs. Ganush the extension she needed. When the rugs were pulled out from under her, however, Christine looked to use any shield she could find; on more than one occasion, upon being accused of committing an amoral act, she insisted that her boss was the one who started everything (he was, indeed, as part of the system that enabled her action, but the ultimate decision was hers to make). She let others put themselves at risk for her. To her credit, she showed herself to be a woman of some principle – another person may not have hesitated as much as she did with her decisions, and may not have thought twice about the fate of the cursed button. Guilt sometimes can inspire such great moral acts.

As a modern woman, she also showed much self-reliance and resourcefulness. Even when she was cornered, she either did not rely on help from her man (her pawning everything she owned to help herself was touching and surprising), or was left by chance (fate?) to fend for herself (the phone call would not come through). In some ways, sadly, she was all the defense she had, but being alone did not make her a special case. Rham Jas referred to Christine once as an “insignificant” person, and it deflated the sense of self-importance some social climbers have of themselves. In the context of a horror genre, it was unusual to have a protagonist not be specifically ‘chosen’ for a role. When ordinary characters are cast, they would often be given opportunities to do extraordinary things. This would have been an easy way for the audience to feel good about themselves and their fellow beings – who doesn’t want to be inspired? The fact that Christine was not a special case made her special in the larger context, ironically. Unfortunately for Christine, being ordinary did not do her any favours when it came to dealing with the extraordinary. The events in the film seemed to also point to true morality revealing itself only in the heat of fire, and that some of the people who would not live up to this test (that would be most of us) may (or should?) not get away with their slip on the moral compass.

Because of these complexities, Christine inadvertently became more interesting and unusual in the context of the genre: the audience may find themselves feeling ambivalence towards her fate, as she would gain and lose sympathy, sometimes within a few frames (Lohman was superb at embodying these shades of grey). Being a modern woman is never quite completely good and moral as often demanded of characters in horror films, and it is rare that a film existing in fantasy would be inspiring with its choice of such a realistic (or at least close to being as such) lead. The filmmakers may have been overly critical of this particular modern woman, but in doing so, they made her one of the most fascinating and complex leads to watch in a genre that’s not particularly known for depth. In turn, she made the film surprisingly more substantial and interesting than all the fun gags could reveal.

Clip:

Subscribe

Subscribe

No Response to "Drag me to hell (Raimi, 2009): A modern woman dragged to hell"

Post a Comment